What Is Wasabi and Why Is This Traditional Japanese Culinary Herb Used for Digestive Support and Antimicrobial Balance?

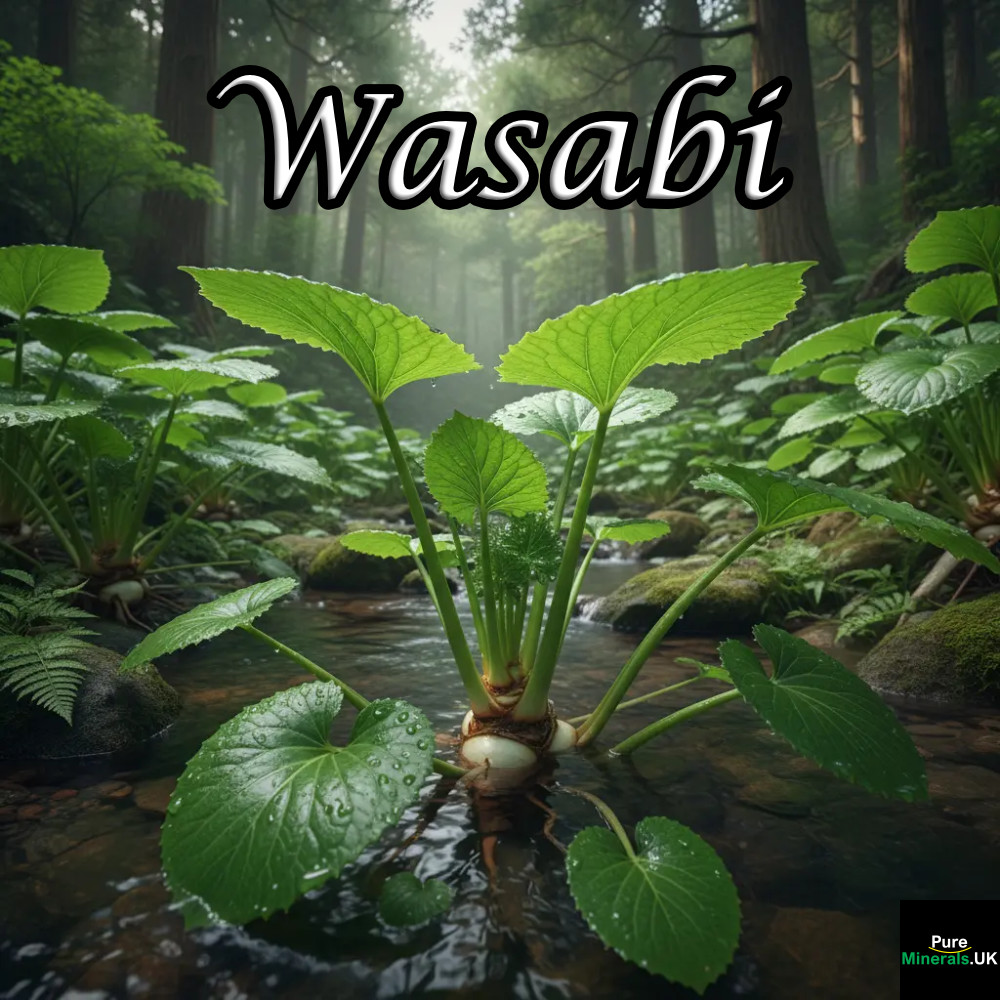

Wasabi is a traditional Japanese culinary herb valued for its sharp flavour and its supportive effects on digestion and food hygiene. Derived from the rhizome of a freshwater plant native to Japan, wasabi has long been used alongside raw fish and seafood, where its pungent compounds contribute to both flavour and functional food use. In herbal contexts, wasabi is considered a food-herb rather than a medicinal tonic.

Definition:

Wasabi is the rhizome of Wasabia japonica (also known as Eutrema japonicum), containing sulphur-based compounds known as isothiocyanates. These compounds are responsible for wasabi’s distinctive heat and its traditional use in supporting digestion and microbial balance.

Extended Definition:

Unlike chilli heat, which comes from capsaicin, wasabi’s pungency arises from allyl isothiocyanate and related compounds released when the fresh rhizome is grated. These volatile compounds stimulate the nasal passages rather than the tongue and dissipate quickly. Traditionally, wasabi has been used to support digestion by stimulating digestive secretions and enhancing appetite, particularly when consumed with protein-rich foods.

Wasabi has also been valued for its role in food hygiene, especially in traditional Japanese cuisine, where it accompanies raw fish. Its natural antimicrobial properties were historically believed to help limit spoilage and microbial exposure. Nutritionally, wasabi provides small amounts of vitamin C, potassium, and antioxidant compounds, though it is typically consumed in modest quantities. True wasabi is distinct from common commercial “wasabi paste,” which is often a mixture of horseradish, mustard, and colouring.

Key Facts:

- Herb name: Wasabi

- Botanical name: Wasabia japonica (Eutrema japonicum)

- Herb type: Culinary food-herb

- Key compounds: Isothiocyanates (including allyl isothiocyanate)

- Primary uses: Culinary flavour, digestive stimulation, food hygiene support

- Systems supported: Digestive

- Common forms: Freshly grated rhizome, paste, powder

- Use considerations: Authentic wasabi differs from commercial substitutes; heat dissipates rapidly after preparation

- Typical pairing: Traditionally paired with sushi, seafood, soy sauce, and other protein-rich foods

Key Takeaways

- True wasabi offers digestive benefits, antibacterial properties, and anti-inflammatory effects that are more potent than the common imitation made from horseradish.

- The authentic wasabi plant (Wasabia japonica) contains unique isothiocyanates that provide both the distinctive flavor and significant health benefits.

- Wasabi’s traditional pairing with raw fish isn’t coincidental—it naturally helps protect against food-borne pathogens, supporting food safety practices.

- Real Wasabi offers premium-quality, authentic wasabi products that preserve both the cultural tradition and health benefits of this remarkable Japanese root.

- Beyond sushi, wasabi can enhance everything from dressings to grilled meats while providing digestive enzyme stimulation and potential cardiovascular benefits.

That fiery green paste accompanying your sushi has been hiding secrets. Most diners have never experienced authentic wasabi, despite its revered place in Japanese culinary tradition and impressive health profile.

The pungent kick that clears your sinuses while eating sushi is just the beginning of wasabi’s story. This remarkable rhizome has been valued in Japanese cuisine for over a thousand years, not only for its distinctive flavor but for its numerous health-supporting properties. Real Wasabi brings this authentic culinary tradition to discerning food enthusiasts who appreciate both the complex flavor and functional benefits of genuine wasabi.

Real Wasabi vs. The Green Paste You’ve Been Eating

The truth might surprise you: approximately 95% of “wasabi” served in restaurants worldwide is not wasabi at all. What most people have experienced is a blend of horseradish, mustard, cornstarch, and green food coloring. True wasabi (Wasabia japonica) is a rhizome that grows naturally in rocky mountain streams throughout Japan. Its rarity, growing requirements, and short shelf-life after grating (flavor peaks at 15 minutes and significantly diminishes after) make it an expensive luxury reserved for high-end establishments.

The difference isn’t just in authenticity but in the entire sensory experience. Real wasabi delivers a complex, fresh herbal flavor with a quick heat that dissipates quickly without lingering burn. It’s aromatic, sweet, and earthy with subtle green notes that complement rather than overpower delicate foods. Unlike the artificial version’s harsh, extended burn, authentic wasabi provides a clean, quick heat that enhances rather than masks other flavors.

The Unique Flavor Profile That Makes Wasabi Special

Authentic wasabi presents a symphony of flavors that develops in stages across the palate. The initial taste is surprisingly sweet and vegetal, reminiscent of fresh green peas with subtle earth tones. This quickly builds to its signature pungency—a clean, bright heat that rises through the nasal passages rather than burning the tongue. What makes wasabi truly remarkable is how quickly this intensity fades, leaving behind a pleasant, refreshing sensation without lingering heat.

This complex flavor profile makes wasabi exceptionally versatile in the kitchen. Its ability to deliver intensity without overwhelming other ingredients allows it to complement delicate flavors like raw fish while still cutting through rich, fatty foods. The ephemeral nature of its heat means it can be enjoyed repeatedly throughout a meal without palate fatigue.

Wasabi’s distinctive chemical composition creates this unique sensory experience. Its active compounds—various isothiocyanates—are volatile, meaning they evaporate quickly. This explains both the rapid onset and quick dissipation of wasabi’s heat, as well as why freshly grated wasabi loses its potency within 15-30 minutes.

The Science Behind Wasabi’s Signature Nasal Kick

The unforgettable sinus-clearing sensation that accompanies wasabi consumption isn’t actually detected by taste buds. Instead, specific compounds in wasabi—primarily allyl isothiocyanate—directly stimulate the trigeminal nerve, which is responsible for facial sensations. This nerve activation creates the distinctive “wasabi rush” that travels up through the nasal passages rather than lingering on the tongue like capsaicin-based heat from chili peppers.

This unique mechanism explains why wasabi heat feels fundamentally different from other spicy foods. The sensation travels through different neural pathways, creating a brief but intense experience that affects the upper sinuses and even stimulates tear production in some cases. Interestingly, this same compound provides many of wasabi’s health benefits, acting as a natural antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory agent in the body.

How Authentic Wasabi Differs From Common Imitations

Beyond flavor, real wasabi contains a more complex array of bioactive compounds than its horseradish-based substitute. Authentic wasabi contains at least four different isothiocyanates, each with unique properties, while imitation wasabi primarily contains just one (allyl isothiocyanate). This diversity of compounds contributes to wasabi’s more nuanced flavor profile and expanded health benefits.

Visual Comparison: Real wasabi paste has a naturally pale green color with visible texture from the freshly grated rhizome. Imitation wasabi appears uniformly bright green with a smooth consistency due to food coloring and processing.

The cultivation of authentic wasabi remains a specialized art. Traditional wasabi farms feature flowing mountain spring water over carefully arranged river rocks where the wasabi plants grow semi-submerged. This labor-intensive growing process contributes to real wasabi’s limited availability and higher price point, but results in a product with superior flavor complexity and health benefits that simply cannot be replicated by substitutes.

Five Traditional Japanese Culinary Uses For Wasabi

In Japanese cuisine, wasabi transcends its familiar role as sushi’s companion. For centuries, Japanese chefs have incorporated this prized rhizome into diverse culinary applications that showcase both its flavor complexity and functional benefits. Understanding these traditional uses provides insight into wasabi’s versatility beyond the sushi counter.

The cultural significance of wasabi in Japanese cuisine cannot be overstated. Its careful cultivation and preparation reflect Japan’s meticulous approach to ingredients, where quality and proper technique are paramount. Many traditional wasabi preparations remain unchanged for generations, preserving authentic flavor experiences that connect modern diners with centuries of culinary heritage.

1. Sushi and Sashimi Companion

The most recognized application of wasabi is with raw fish, but traditional Japanese sushi chefs employ it with sophisticated restraint. Rather than providing wasabi as a side condiment, authentic sushi preparation involves placing a small amount directly between the fish and rice. This technique allows the wasabi’s aromatic compounds to enhance the fish’s natural flavors without overwhelming them.

The marriage between wasabi and raw fish serves both culinary and practical purposes. While enhancing flavor, wasabi’s natural antimicrobial properties help neutralize potential pathogens in raw seafood. This functional benefit explains why wasabi became historically inseparable from raw fish preparations, creating both a flavor enhancement and a traditional food safety measure.

2. Soba Noodle Flavor Enhancer

Cold soba noodles frequently feature wasabi as a flavor accent in traditional Japanese dining. The earthy buckwheat flavor of soba pairs remarkably well with wasabi’s clean heat, creating a refreshing dish perfect for hot summer days. Typically, a small amount of freshly grated wasabi is mixed into the dipping sauce or placed on the side of the dish for diners to add according to preference. For those interested in other natural flavorings, nettle can also be explored as a unique ingredient in various dishes.

The wasabi-soba combination demonstrates how wasabi can enhance non-seafood dishes through thoughtful application. The noodles’ subtle flavor provides a neutral canvas that allows wasabi’s complexity to shine without competition, while the dish’s simplicity showcases wasabi’s ability to transform basic ingredients into memorable culinary experiences.

3. Wasabi Salt For Grilled Meats

A traditional preparation called wasabi-shio (wasabi salt) combines finely grated wasabi with high-quality sea salt to create a seasoning for grilled meats and vegetables. This versatile condiment adds depth to simple preparations like grilled chicken, beef, or seasonal vegetables. The salt’s crystalline structure captures wasabi’s volatile compounds, preserving its flavor longer than fresh wasabi paste.

Wasabi salt exemplifies how Japanese cuisine often creates complex flavors from minimal ingredients through careful technique. The preparation transforms both components—the salt carries wasabi’s aromatics more efficiently, while the wasabi moderates the salt’s intensity. This balance creates a seasoning that enhances food without dominating it, following the Japanese culinary principle of letting ingredients’ natural qualities shine.

4. Component in Traditional Dipping Sauces

Beyond sushi, wasabi appears in numerous Japanese dipping sauces and condiments. Ponzu, a citrus-soy dipping sauce, often includes a small amount of wasabi to brighten the flavor. Similarly, traditional shabu-shabu (hot pot) dipping sauces frequently feature wasabi as a key component, cutting through the richness of the cooked meats and adding aromatic complexity.

These diverse sauce applications demonstrate wasabi’s remarkable ability to harmonize with other strong flavors. When paired with soy sauce, wasabi’s pungency finds balance with umami richness. With citrus, wasabi highlights the fruit’s brightness while tempering its acidity. These complementary relationships explain why wasabi has remained essential in Japanese sauce-making for centuries.

5. Palate Cleanser Between Courses

In traditional kaiseki (multi-course) dining, small amounts of wasabi sometimes appear between dishes to refresh the palate. This cleansing function takes advantage of wasabi’s quick-dissipating heat and aromatic properties, which stimulate taste receptors without lingering. The practice helps diners fully appreciate the subtle flavors of subsequent courses without flavor carryover.

This palate-cleansing application highlights wasabi’s unique sensory profile compared to other pungent foods. Unlike chili heat, which builds and persists, wasabi’s intensity peaks quickly then fades completely, making it ideal for resetting taste perception. This quality reflects Japanese cuisine’s emphasis on progression and transition between flavors throughout a meal.

Beyond Japanese Cuisine: Modern Wasabi Applications

Contemporary chefs worldwide have embraced wasabi’s distinctive properties, incorporating it into diverse culinary traditions far beyond its Japanese origins. This global adoption has spawned creative applications that highlight wasabi’s remarkable versatility while respecting its authentic character. From high-end restaurants to home kitchens, wasabi has transcended its traditional boundaries to become a global culinary asset.

The crossover success of wasabi stems from its unique flavor profile that offers intensity without persistent heat. Unlike chili peppers that can dominate a dish, wasabi can deliver a momentary sensation that enhances other ingredients without overwhelming them. This quality makes it exceptionally adaptable to various global cuisines seeking nuanced heat and aromatic complexity.

Modern culinary innovations featuring wasabi generally fall into three categories: infusions that extract wasabi’s compounds into other mediums, unexpected pairings that create novel flavor combinations, and techniques that showcase wasabi in non-traditional formats and textures. Each approach demonstrates wasabi’s remarkable culinary flexibility while preserving its distinctive character.

Wasabi-Infused Oils and Dressings

Chefs have discovered that wasabi’s volatile compounds can be captured in fats, creating aromatic oils and emulsions that distribute wasabi’s flavor throughout a dish. Wasabi-infused olive oil drizzled over seafood or finishing a risotto provides subtle wasabi notes without the texture of the paste. Similarly, wasabi-enhanced vinaigrettes bring brightness to salads while introducing wasabi’s distinctive flavor profile in an unexpected format.

These infusion techniques solve one of wasabi’s biggest culinary challenges: its quickly fading flavor. By binding wasabi compounds to fat molecules, these preparations help preserve the distinctive flavor longer than fresh wasabi paste would maintain it. The result offers diners a more sustained wasabi experience distributed evenly throughout the eating experience rather than concentrated in individual bites.

Western Adaptations in Fine Dining

Progressive Western chefs have incorporated wasabi into unexpected applications that showcase its versatility beyond Asian contexts. Wasabi-infused mashed potatoes pair remarkably well with seared scallops, creating a temperature contrast that highlights both components. Some innovative pastry chefs have even introduced wasabi into desserts, where its clean heat provides a counterpoint to sweet elements in chocolate or fruit preparations.

The fine dining approach to wasabi often involves deconstructing its sensory experience and rebuilding it in new contexts. Some chefs separate wasabi’s aromatic components from its heat through different preparations, allowing diners to experience these qualities independently before they merge on the palate. Others focus on texture transformations, creating wasabi powders, foams, or gels that deliver the familiar flavor through unfamiliar physical forms.

Cocktails and Beverages With Wasabi Kick

The beverage world has embraced wasabi as a dynamic ingredient in both alcoholic and non-alcoholic drinks. Wasabi-infused spirits form the base of specialty cocktails, particularly in variations of the Bloody Mary and martinis, where wasabi’s heat complements savory or citrus elements. Non-alcoholic applications include wasabi-ginger lemonades and green tea infusions, where wasabi adds complexity and stimulating qualities without overwhelming the primary flavors.

Wasabi’s Powerful Digestive Benefits

The distinctive heat from wasabi does more than wake up your taste buds—it activates a cascade of digestive processes that can significantly improve nutrient absorption and gut function. Unlike chili peppers that primarily affect the mouth, wasabi’s active compounds target the digestive system directly, stimulating the production of digestive juices and promoting healthy gut activity. For additional digestive support, consider the benefits of slippery elm, which is known for its soothing properties on the digestive tract.

Traditional Japanese medicine has long recognized wasabi’s digestive benefits, using it to address various gastrointestinal complaints for centuries before modern science confirmed these effects. This functional aspect explains why wasabi traditionally accompanies foods that are either fatty (like some fish) or difficult to digest—it helps the body process these challenging foods more efficiently.

How Wasabi Stimulates Digestive Enzymes

Wasabi’s isothiocyanates trigger increased production of digestive enzymes throughout the digestive tract. This enzymatic boost begins in the mouth, where wasabi stimulates saliva production containing amylase for initial starch breakdown. The effect continues in the stomach, where wasabi compounds prompt increased gastric juice secretion containing pepsin for protein digestion, and in the pancreas, which releases additional digestive enzymes in response to wasabi consumption.

This multi-level enzyme stimulation creates a comprehensive digestive aid that addresses multiple food components simultaneously. For individuals with sluggish digestion or those consuming particularly rich meals, wasabi’s enzyme-stimulating effects can significantly reduce post-meal discomfort and improve overall nutrient extraction from food.

Bloating Relief Properties

Many people experience reduced bloating and gas when incorporating wasabi into meals, particularly those containing difficult-to-digest components like beans or certain vegetables. The volatile compounds in wasabi appear to help regulate gut bacteria populations while reducing fermentation that can lead to uncomfortable gas production. These anti-bloating effects make wasabi particularly valuable for individuals prone to digestive discomfort after meals.

Wasabi’s digestive benefits extend beyond immediate comfort to support overall gut health. Regular consumption may help maintain optimal gut flora balance by selectively inhibiting harmful bacteria while preserving beneficial populations. This prebiotic-like effect contributes to wasabi’s reputation as a digestive tonic in traditional Japanese wellness practices.

The Food Safety Connection: Why Wasabi Is Paired With Raw Fish

Wasabi’s traditional pairing with raw fish isn’t merely a flavor preference—it represents one of history’s most elegant examples of functional food pairing. Long before refrigeration or modern food safety knowledge, Japanese culinary tradition recognized that wasabi helped prevent foodborne illness associated with raw seafood consumption. This intuitive understanding preceded scientific confirmation by centuries but has been thoroughly validated by modern research.

The antimicrobial properties of wasabi provided critical protection in an era before modern food preservation. This traditional wisdom demonstrates remarkable insight into natural food safety measures and offers a fascinating glimpse into how culinary traditions often contain hidden functional benefits discovered through generations of observation. For more insights into traditional herbs with functional benefits, explore the uses of slippery elm.

Antibacterial Properties Against Food-Borne Pathogens

Research confirms that wasabi contains potent compounds effective against common food-borne bacteria, including E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and certain Vibrio species frequently associated with seafood contamination. The primary active compounds—various isothiocyanates—demonstrate significant antibacterial effects even at relatively low concentrations, helping reduce pathogen risk in raw fish preparations.

These antibacterial effects work through multiple mechanisms, including disrupting bacterial cell membranes, interfering with bacterial protein function, and inhibiting bacterial enzyme systems necessary for pathogen survival. While modern food safety practices remain essential, wasabi provides an additional layer of protection that complements proper handling and storage of raw fish.

Historical Uses as a Food Preservative

Beyond its immediate antibacterial effects during consumption, wasabi served as a functional food preservative in traditional Japanese cuisine. Fish vendors would often incorporate wasabi between layers of fish or wrap fish with wasabi-treated leaves to extend freshness before refrigeration was available. This preservation technique took advantage of wasabi’s volatile compounds that could permeate the fish tissue and inhibit bacterial growth during storage and transport.

Similar preservation applications extended to other perishable foods, with wasabi leaves sometimes wrapped around rice balls (onigiri) or other prepared foods to delay spoilage. These historical practices demonstrate wasabi’s practical importance beyond flavor, serving crucial food safety functions in traditional Japanese food systems.

Health Benefits Beyond Digestion

Wasabi’s contributions to well-being extend far beyond its digestive and antimicrobial properties. Modern research has identified numerous bioactive compounds in wasabi that support multiple body systems, from cardiovascular function to cellular health. These findings align with traditional Japanese medicine, which has long employed wasabi as a therapeutic agent for various health conditions.

The nutritional profile of wasabi includes not only its signature isothiocyanates but also essential vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients that contribute to overall health. While wasabi isn’t typically consumed in large quantities, its concentrated bioactivity means even small amounts can provide meaningful health benefits when included regularly in the diet.

Anti-Inflammatory Effects

Wasabi contains powerful anti-inflammatory compounds that help modulate the body’s inflammatory response. These effects stem primarily from 6-methylsulfinylhexyl isothiocyanate (6-MSITC), a compound relatively unique to wasabi that demonstrates significant anti-inflammatory activity. Research suggests these compounds may help reduce inflammation associated with various chronic conditions and support overall immune system balance.

The anti-inflammatory mechanism differs from conventional anti-inflammatory medications, working primarily through antioxidant pathways and NF-κB signaling inhibition. This distinctive approach to inflammation regulation may provide benefits without the side effects associated with some pharmaceutical anti-inflammatories, making wasabi a valuable complement to an anti-inflammatory diet.

Potential Cancer-Fighting Properties

Multiple studies have identified cancer-protective properties in wasabi compounds, particularly in relation to stomach, colorectal, and certain other cancers. These effects appear linked to wasabi’s ability to induce Phase II detoxification enzymes that help neutralize potential carcinogens before they can damage cells. Additionally, certain wasabi compounds demonstrate direct anti-cancer activity by promoting apoptosis (programmed cell death) in abnormal cells while leaving healthy cells untouched.

While research continues to explore these promising properties, wasabi’s potential cancer-protective effects provide another compelling reason to incorporate this functional food into a health-supportive diet. These benefits align with observations from population studies showing lower cancer rates in regions with high wasabi consumption, though multiple dietary and lifestyle factors likely contribute to these patterns.

Cardiovascular System Support

Wasabi offers notable cardiovascular benefits through multiple mechanisms affecting blood vessel health and blood platelet function. Its compounds help inhibit abnormal platelet aggregation—the excessive blood clumping that can lead to dangerous clots—without interfering with normal clotting function. This selective antiplatelet effect may help maintain healthy circulation while reducing clot-related risks.

Additional cardiovascular benefits include wasabi’s potential to support healthy blood pressure through vasodilation effects and its ability to reduce oxidation of LDL cholesterol, a key factor in atherosclerosis development. These cardiovascular protective properties make wasabi particularly valuable for individuals concerned with heart health, though they complement rather than replace conventional cardiovascular care.

How to Prepare and Store Fresh Wasabi

Unlocking the full potential of wasabi begins with proper preparation and storage techniques that preserve its volatile compounds and distinctive flavor profile. Whether working with fresh rhizomes or quality prepared products, understanding these principles helps maximize both culinary enjoyment and health benefits from this remarkable plant.

Finding Real Wasabi Root

Securing authentic wasabi rhizomes requires some effort but yields incomparable results. Specialty Asian markets, high-end grocery stores, and online suppliers that focus on Japanese ingredients occasionally offer fresh wasabi rhizomes, though availability remains limited due to cultivation challenges. When selecting fresh wasabi, look for firm rhizomes with vibrant green flesh when cut and no soft spots or discoloration.

If fresh rhizomes prove inaccessible, several companies now offer freeze-dried wasabi powder made from 100% real wasabi, providing a more authentic alternative to common horseradish-based substitutes. These products retain many of the beneficial compounds and much of the flavor complexity of fresh wasabi, though with somewhat reduced aromatic intensity.

For those truly dedicated to authentic wasabi, some specialty suppliers like Real Wasabi offer premium wasabi products that maintain traditional growing methods and processing techniques, ensuring the highest quality experience and maximum health benefits.

Traditional Grating Techniques

Proper wasabi preparation involves finely grating the rhizome using a traditional sharkskin grater (oroshigane) or ceramic equivalent with very fine teeth. The grating process ruptures the cell walls, allowing enzymes to mix with precursor compounds and create the volatile isothiocyanates responsible for wasabi’s flavor and benefits. This reaction occurs only after grating—intact wasabi contains virtually no heat or aroma until its cellular structure is disrupted.

Storage Methods to Preserve Flavor

Fresh wasabi rhizomes require careful storage to maintain quality and extend usability. Wrap unwashed rhizomes in damp paper towels, place in a perforated plastic bag, and store in the refrigerator’s vegetable drawer. Change the damp towels every few days to prevent mold while maintaining necessary humidity. Properly stored, fresh wasabi rhizomes can maintain quality for 2-3 weeks.

For prepared wasabi paste, minimize oxygen exposure by pressing plastic wrap directly onto the surface before sealing in an airtight container. Even with optimal storage, prepared wasabi begins losing potency within 15-30 minutes after preparation, with significant degradation occurring after a few hours as the volatile compounds dissipate.

Making the Most of Wasabi Paste When Fresh Isn’t Available

When fresh wasabi remains inaccessible, quality prepared products can still provide enjoyable flavor and beneficial compounds, though with some compromise in aromatic complexity and intensity. The key lies in selecting products with the highest possible wasabi content and minimal additives, then employing preparation techniques that maximize the remaining compounds.

Understanding that even premium prepared wasabi pastes contain some proportion of horseradish helps set appropriate expectations while still appreciating the unique qualities these products offer. With proper selection and handling, these convenient alternatives can deliver satisfying culinary experiences that capture much of wasabi’s distinctive character. For those interested in exploring other natural ingredients, consider learning about nettle and its uses in various culinary applications.

Quality Indicators in Prepared Wasabi Products

When evaluating prepared wasabi options, prioritize products listing wasabi rhizome (Wasabia japonica) as the first ingredient rather than horseradish. Avoid products containing artificial colors, excessive preservatives, or sweeteners that mask wasabi’s natural flavor profile. The best commercial options typically come from Japanese manufacturers with traditional wasabi expertise, though some Western specialty producers now create high-quality wasabi products.

Mixing Tips for Optimal Flavor Development

To maximize prepared wasabi’s flavor, mix powder with cold water to form a paste, then cover and let rest 5-10 minutes before using to allow flavor compounds to develop fully. For tube wasabi, squeeze a small amount onto a plate and let sit briefly exposed to air before using, which allows some volatile compounds to activate. Both methods help simulate some of the aromatic complexity found in freshly grated wasabi.

Transform Your Meals With These Wasabi Techniques

Incorporating wasabi into everyday cooking opens new dimensions of flavor while providing its numerous health benefits. Beyond sushi, wasabi’s distinctive character enhances everything from breakfast eggs to dinner entrees. The key lies in thoughtful application—using wasabi to complement rather than dominate other flavors while considering how its volatile nature affects the overall dish.

Experimenting with wasabi allows home cooks to discover personal preferences for intensity and pairing. Start with small amounts in familiar recipes, then gradually explore more adventurous applications as your palate adapts to wasabi’s unique profile. The following techniques offer entry points for incorporating this versatile ingredient into diverse culinary contexts.

Culinary Application | Technique | Health Benefit |

|---|---|---|

Avocado Toast | Mix a small amount of wasabi into mashed avocado | Enhanced digestion of healthy fats |

Grilled Steak | Create wasabi compound butter as a finishing touch | Improved protein breakdown |

Salad Dressing | Whisk wasabi into the vinaigrette | Antimicrobial protection for raw vegetables |

Mashed Potatoes | Incorporate wasabi paste during final mixing | Reduced bloating from starchy foods |

Smoked Salmon | Serve with wasabi-cream cheese blend | Food safety enhancement for preserved fish |

Even beyond these specific applications, wasabi can enhance virtually any dish that benefits from a bright, clean heat without lingering burn. Its ability to cut through richness makes it particularly valuable with fatty foods, while its aromatic complexity adds dimension to otherwise simple preparations. The brief intensity of wasabi heat allows it to serve as a flavor accent without dominating the overall eating experience.

Important Note:

Wasabi is traditionally consumed as a culinary food-herb in small amounts. Authentic wasabi differs from many commercial substitutes, which often contain horseradish and mustard. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent disease.

Frequently Asked Questions

Wasabi generates many questions from both culinary enthusiasts and health-conscious consumers looking to understand this unique ingredient better. The following responses address common inquiries about wasabi’s authenticity, preparation, health impacts, and culinary applications based on current research and traditional knowledge.

Is the wasabi served in most sushi restaurants real?

No, approximately 95% of wasabi served in restaurants worldwide (including in Japan) is actually a substitute made from horseradish, mustard powder, and green food coloring. Real wasabi is expensive (about $70-$100 per pound), difficult to cultivate, and loses flavor rapidly after grating. High-end Japanese restaurants sometimes offer genuine wasabi for an additional charge, but it remains rare even in specialty establishments. For those looking for alternatives, ingredients like horseradish are often used as substitutes in many dishes.

How long does fresh wasabi paste maintain its flavor after grating?

Fresh wasabi reaches peak flavor approximately 5-10 minutes after grating as the enzymatic reactions fully develop. After this peak, the volatile compounds begin dissipating rapidly, with significant flavor loss occurring within 15-30 minutes. Within 1-2 hours, most of the distinctive aromatic compounds will have evaporated, leaving behind a much milder paste with diminished complexity. This short flavor window explains why traditional sushi chefs grate wasabi immediately before serving.

Can people with certain health conditions benefit from eating wasabi?

Research suggests that wasabi may offer particular benefits for several health conditions, including respiratory issues (where its volatile compounds help clear sinuses), digestive disorders (through enzyme stimulation and anti-inflammatory effects), and circulatory concerns (via its anti-platelet aggregation properties). However, individuals with specific medical conditions should consult healthcare providers before using wasabi therapeutically, as its compounds may interact with certain medications or aggravate some conditions like gastric ulcers or specific inflammatory disorders.

What’s the best way to tame wasabi’s heat if it’s too intense?

Unlike chili pepper heat that builds and lingers, wasabi’s intensity peaks quickly and then fades rapidly on its own. If wasabi heat becomes uncomfortable, dairy products like milk or yogurt help neutralize the sensation, as do starchy foods like rice. Sweet flavors can also counterbalance wasabi’s pungency effectively. Remember that authentic wasabi provides a cleaner, briefer heat than horseradish-based substitutes, which tend to produce a harsher, more persistent burn.

Are there any side effects or concerns with consuming wasabi regularly?

For most people, moderate wasabi consumption presents no significant concerns. However, individuals with gastric ulcers, certain inflammatory conditions, or those taking blood-thinning medications should exercise caution due to wasabi’s anti-inflammatory and anti-platelet effects. Those with thyroid disorders should consult healthcare providers, as compounds in cruciferous vegetables (including wasabi) may affect thyroid function in sensitive individuals when consumed in large amounts. As with any potent food, moderation remains key to enjoying wasabi’s benefits without unwanted effects.

Wasabi’s remarkable properties extend far beyond its role as sushi’s sidekick. From its digestive benefits to its food safety applications, this distinctive rhizome offers a powerful combination of culinary excitement and functional health support. By understanding both its traditional uses and modern applications, you can harness wasabi’s full potential in your kitchen and wellness routine.

For those interested in experiencing the authentic flavor and maximum health benefits of real wasabi, Real Wasabi offers premium products cultivated using traditional methods that preserve this remarkable plant’s full spectrum of compounds and sensory characteristics.

Wasabi is not just a spicy condiment for sushi; it has a range of culinary uses and potential health benefits. Some studies suggest that wasabi may aid in digestion and provide antimicrobial properties, making it a valuable addition to meals for both flavor and health. Its unique compounds are also being researched for their ability to support digestive health, similar to other natural remedies like slippery elm, which is known for its soothing effects on the digestive tract.