Key Takeaways

- Gingerol, the main bioactive compound in fresh ginger, provides most of its health benefits and pungent flavor

- Regular consumption of gingerol-rich ginger may improve cardiovascular health by enhancing blood circulation and reducing inflammation

- Fresh ginger contains higher concentrations of gingerol than dried or cooked ginger, maximizing health benefits

- Gingerol activates TRPV1 receptors in your body, creating the warming sensation and triggering various physiological responses

- Adding just a small amount of fresh ginger to your daily diet can provide significant anti-inflammatory and digestive benefits

That distinctive warmth that spreads through your body after sipping ginger tea isn’t just a pleasant sensation—it’s your circulation getting a natural boost. Gingerol, the primary bioactive compound in fresh ginger, does much more than add spicy flavor to your favorite dishes. This powerful compound has been linked to numerous health benefits that have made ginger a staple in traditional medicine systems worldwide for thousands of years. Modern research continues to validate these traditional uses, revealing how gingerol’s unique molecular structure interacts with our bodies to improve health in multiple ways.

Understanding the science behind gingerol’s effects can help you make more informed choices about how to incorporate this powerful plant compound into your wellness routine. Whether you’re looking to improve circulation, reduce inflammation, or simply enjoy its culinary applications, gingerol offers a fascinating intersection of flavor and function that few natural compounds can match.

Ginger’s Spicy Secret: What Makes This Root So Powerful

The humble ginger root houses a complex pharmacy of beneficial compounds, with gingerols standing out as the star performers. These phenolic compounds are responsible for ginger’s characteristic pungency and most of its therapeutic effects. While ginger contains hundreds of compounds, including essential oils and other phenols, it’s the gingerol content—particularly 6-gingerol—that researchers have identified as the most pharmacologically active.

What makes gingerol particularly interesting is how it interacts with our sensory system. Unlike the capsaicin in hot peppers that creates a burning sensation, gingerol produces a more warming, diffuse heat that spreads throughout the body. This difference isn’t just about sensory experience—it reflects how these compounds interact with our physiology in fundamentally different ways.

The concentration of gingerol varies significantly based on the form of ginger you consume. Fresh ginger root contains the highest levels, with concentrations declining when the root is dried, cooked, or processed. This is why fresh ginger delivers that signature spicy kick that may be noticeably reduced in dried ginger powder or after cooking.

The Science Behind Gingerol: Ginger’s Star Compound

At the molecular level, gingerol has a structure that allows it to interact with various cellular receptors and signaling pathways in the human body. This versatility explains gingerol’s wide range of biological effects, from pain relief to nausea reduction. The compound belongs to the vanilloid family, which includes other bioactive substances like capsaicin and zingerone.

What makes gingerol particularly potent is its ability to influence multiple physiological systems simultaneously. It’s not just an anti-inflammatory agent or a circulatory stimulant—it’s both, and more. This multi-target activity makes gingerol more effective than many isolated compounds that might affect only one pathway in the body.

Chemical Structure of Gingerol and How It Differs from Other Spicy Compounds

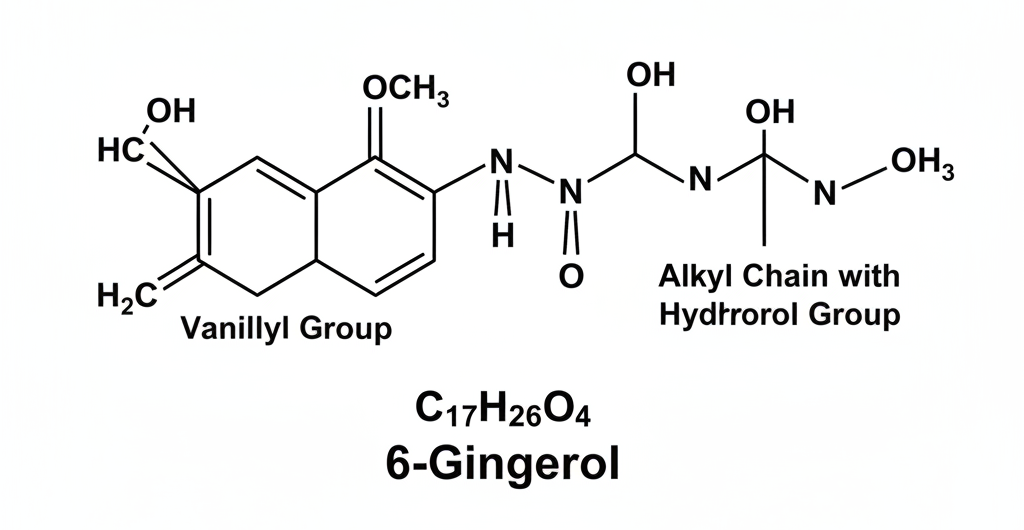

Two-dimensional chemical structure of the molecule 6-gingerol, featuring the vanillyl group and the six-carbon alkyl chain with the hydroxyl group.

Chemically speaking, gingerol (specifically 6-gingerol) is a phenylpropanoid with a hydrocarbon tail and a vanillyl group. This structure shares similarities with capsaicin but has crucial differences that create its unique effects. While both compounds activate heat and pain receptors, gingerol does so more mildly and transiently. The slight variations in their molecular structures lead to significantly different interactions with our body’s receptors, explaining why ginger produces a warming sensation rather than the intense heat of chili peppers. For more detailed information, you can explore this scientific study on gingerol.

How Gingerol Activates TRPV1 Receptors in Your Body

The warming sensation you experience when consuming ginger comes from gingerol’s interaction with TRPV1 receptors (transient receptor potential vanilloid 1). These receptors act as the body’s thermometers and pain sensors, normally responding to temperatures above 109°F (43°C). When gingerol binds to these receptors, it tricks them into thinking they’re experiencing heat, even at normal body temperature. This activation not only creates the warming sensation but also triggers a cascade of physiological responses, including increased blood flow and mild anti-inflammatory effects.

What’s fascinating is that this receptor activation doesn’t just create a subjective feeling of warmth—it stimulates real physiological changes in blood vessel dilation and increased circulation. Your body responds to the perceived heat by increasing blood flow to the affected areas, which may help deliver nutrients and remove waste products more efficiently.

Why Fresh Ginger Packs More Heat Than Dried or Cooked Ginger

The pungency difference between fresh and processed ginger directly relates to gingerol content and transformation. When exposed to heat during cooking or drying processes, gingerol undergoes a molecular transformation, converting partially into zingerone and shogaol. While these compounds still offer health benefits, they interact differently with our taste receptors and TRPV1 channels.

Fresh ginger typically contains 1-3% gingerol by weight, while dried ginger might contain significantly less active gingerol but increased levels of shogaol. This chemical transformation explains why dried ginger has a different flavor profile—less pungent but often described as having a spicier, more complex heat. For maximum gingerol content and its associated benefits, using fresh ginger is the optimal choice, particularly when seeking its circulatory and anti-inflammatory effects.

How Gingerol Boosts Your Circulation

Gingerol’s impact on blood circulation is one of its most remarkable and immediately noticeable effects. When consumed, this compound triggers a cascade of physiological responses that dilate blood vessels, reduce blood pressure, and improve overall blood flow. These effects make ginger a natural circulation enhancer that works through multiple mechanisms simultaneously.

The circulatory benefits aren’t just theoretical—they’ve been observed in numerous clinical studies. Research has shown that regular ginger consumption can reduce platelet aggregation (the clumping together of blood cells), helping blood move more freely through vessels and potentially reducing the risk of dangerous clots.

Immediate Blood Flow Effects After Consuming Ginger

Within minutes of consuming gingerol-rich ginger, you may notice a warming sensation spreading throughout your body. This isn’t just a subjective feeling—it’s the result of peripheral vasodilation, where blood vessels near your skin’s surface expand slightly. This immediate response increases blood flow to your extremities and can be particularly noticeable in fingers, toes, and other areas that might normally have restricted circulation.

The speed of this response makes ginger particularly useful for quickly addressing cold hands and feet or for warming up after exposure to cold temperatures. Unlike alcohol, which can cause temporary vasodilation followed by vasoconstriction, gingerol’s effects are gentler and more sustained, making it a healthier option for improving circulation.

Gingerol’s Role in Widening Blood Vessels

At the molecular level, gingerol promotes vasodilation by influencing nitric oxide production and calcium channel activity in vascular smooth muscle. By inhibiting calcium influx into cells and encouraging the release of nitric oxide (a potent vasodilator), gingerol effectively relaxes blood vessel walls. This relaxation allows vessels to expand, reducing resistance to blood flow and potentially lowering blood pressure.

What’s particularly valuable about this mechanism is that it targets areas where improved circulation is most needed. Unlike some pharmaceutical vasodilators that affect all blood vessels equally, gingerol seems to have a more targeted effect on areas with restricted flow, helping to normalize circulation throughout the body.

The Warming Sensation Explained: What’s Actually Happening in Your Body

The warming effect you feel after consuming ginger isn’t just psychological—it represents real thermogenic activity. When gingerol binds to TRPV1 receptors, it triggers not only vasodilation but also a mild increase in metabolic rate. Your body responds to the perceived heat by increasing blood flow and slightly raising your core temperature, creating that comfortable warming sensation that makes ginger tea so appealing on cold days.

This thermogenic effect may also contribute to ginger’s potential weight management benefits. By temporarily increasing metabolic rate, gingerol may help the body burn slightly more calories, though this effect shouldn’t be overstated. The primary benefit remains improved circulation, which supports overall metabolic efficiency.

Long-Term Cardiovascular Benefits of Regular Ginger Consumption

Beyond the immediate circulatory effects, regular consumption of gingerol may contribute to long-term cardiovascular health. Studies have shown that consistent ginger intake is associated with reduced LDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels, while potentially increasing beneficial HDL cholesterol. These lipid-modifying effects, combined with improved circulation, may reduce overall cardiovascular risk factors.

The anti-inflammatory properties of gingerol also play a crucial role in its cardiovascular benefits. By reducing systemic inflammation, a known contributor to arterial plaque formation, gingerol may help maintain healthier blood vessels and reduce the risk of atherosclerosis. These combined effects make ginger a valuable addition to heart-healthy dietary patterns.

Proven Health Benefits of Ginger’s Active Compounds

Beyond its circulatory effects, gingerol demonstrates an impressive range of health benefits supported by both traditional wisdom and modern scientific research. From managing inflammation to supporting digestive health, the evidence for ginger’s therapeutic potential continues to grow, placing it among the most well-studied and validated medicinal plants.

- Reduces inflammation through multiple pathways, inhibiting pro-inflammatory enzymes

- Alleviates nausea and vomiting associated with pregnancy, chemotherapy, and motion sickness

- Supports digestive function by stimulating gastric emptying and enzyme production

- Shows promising anti-cancer properties in laboratory and animal studies

- May help manage pain conditions, including arthritis and menstrual discomfort

The breadth of gingerol’s effects stems from its interaction with multiple biological systems simultaneously. Unlike many pharmaceutical compounds designed to target a single receptor or pathway, gingerol’s multi-target approach may offer more balanced therapeutic effects with fewer side effects. Additionally, its anti-inflammatory properties can be compared to those of fenugreek, which is also known for inhibiting pro-inflammatory enzymes.

What makes gingerol particularly valuable is that these benefits come with minimal risk. Even at relatively high doses, ginger compounds show excellent safety profiles, with side effects generally limited to mild digestive discomfort in some individuals. This favorable risk-benefit ratio has contributed to ginger’s growing popularity as a natural health supplement.

Recent research has also begun exploring gingerol’s potential benefits for metabolic health, with preliminary evidence suggesting it may help improve insulin sensitivity and glucose management. While more research is needed in this area, the findings align with traditional uses of ginger for supporting metabolic balance.

Anti-Inflammatory Properties That Rival Over-the-Counter Medications

One of gingerol’s most well-documented benefits is its potent anti-inflammatory activity. Through inhibition of cyclooxygenase enzymes (COX-1 and COX-2) and suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, gingerol reduces inflammation through mechanisms similar to those of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen. What makes gingerol remarkable is that it achieves these effects without the gastrointestinal side effects often associated with pharmaceutical NSAIDs.

- Inhibits production of inflammatory prostaglandins and leukotrienes

- Reduces expression of inflammatory genes through NF-κB pathway modulation

- Neutralizes free radicals with powerful antioxidant activity

- May help reduce muscle pain and soreness after exercise

Clinical studies have demonstrated that regular ginger consumption can reduce inflammatory markers in the blood, including C-reactive protein and interleukins. These effects are particularly relevant for individuals with inflammatory conditions like osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, where gingerol’s action may help reduce pain and improve mobility.

The anti-inflammatory benefits extend beyond joint health, potentially supporting overall systemic health. Since chronic inflammation is implicated in numerous age-related conditions and diseases, including cardiovascular disease and certain cancers, gingerol’s anti-inflammatory properties may contribute to its broad health-promoting effects.

Digestive System Support and Nausea Relief

Gingerol’s effects on the digestive system are among its most well-established benefits. The compound stimulates saliva and bile production while enhancing the activity of digestive enzymes, all of which contribute to improved digestion. These effects explain why ginger has been a traditional remedy for digestive discomfort across numerous cultures for centuries.

Perhaps the most extensively studied digestive benefit of gingerol is its antiemetic (anti-nausea) effect. Clinical research has conclusively demonstrated that ginger can reduce nausea and vomiting associated with pregnancy, chemotherapy, and motion sickness. What’s particularly impressive is that these effects have been observed even in challenging contexts like severe morning sickness and post-surgical recovery.

The antiemetic properties work through multiple mechanisms, including direct effects on the gastrointestinal tract and modulation of neurotransmitters in the central nervous system. Gingerol appears to block certain serotonin receptors in the gut and brain that trigger the nausea response, providing relief without the sedative effects of many pharmaceutical antiemetics.

Immune System Enhancement Through Improved Circulation

The immunomodulatory effects of gingerol represent an exciting frontier in research. By improving circulation and reducing inflammation, gingerol helps optimize immune function throughout the body. Better blood flow means immune cells can move more efficiently to where they’re needed, while the anti-inflammatory properties help prevent excessive immune responses that could damage healthy tissue.

Gingerol also demonstrates antimicrobial properties against various pathogens, including certain bacteria and viruses. These effects, combined with enhanced circulation, may explain why ginger has traditionally been used to support recovery from colds and other minor infections. While not a replacement for medical treatment, these properties make ginger a sensible addition to a diet focused on immune support.

The Heat Transformation: What Happens to Gingerol When You Cook It

The chemistry of ginger undergoes fascinating changes when exposed to heat, significantly altering both its flavor profile and health benefits. When gingerol is heated during cooking or drying processes, it transforms partially into shogaol (which has a spicier taste) and zingerone (which has a sweeter, less pungent flavor). These transformations explain why dried ginger often tastes spicier than fresh, while cooked ginger in dishes may seem milder and sweeter.

Interestingly, these transformed compounds aren’t without their own benefits. Shogaol has demonstrated potent anti-inflammatory and anticancer properties in some studies, sometimes exceeding those of gingerol itself. Zingerone, meanwhile, shows promising antioxidant effects. This means that while the specific compound profile changes with cooking, the overall health benefits may simply shift rather than diminish entirely.

How Heat Converts Gingerol to Zingerone

The conversion of gingerol to zingerone occurs through a series of chemical reactions triggered by heat. This transformation involves the breaking and reforming of chemical bonds within the gingerol molecule, resulting in a compound with different sensory and biological properties. As gingerol loses its hydrocarbon tail during heating, it becomes zingerone, which has a sweeter, less pungent flavor profile.

This transformation is temperature-dependent, with more conversion occurring at higher temperatures or with longer cooking times. At moderate cooking temperatures, you’ll still retain some gingerol while developing zingerone, creating a balanced flavor profile. This explains why gently simmered ginger tea often tastes milder than raw ginger juice.

Why Dried Ginger Tastes Different Than Fresh

The distinctive flavor difference between fresh and dried ginger stems from their different chemical compositions. During the drying process, some gingerol naturally converts to shogaol, which has a more intense, spicier heat. This transformation is why dried ginger powder often delivers a stronger heat sensation than an equivalent amount of fresh ginger, despite having lost some of its initial gingerol content.

The dehydration process also concentrates the remaining compounds, effectively increasing their potency by weight. While fresh ginger contains more water content, dried ginger provides a more concentrated dose of active compounds per teaspoon. For culinary applications, this means dried ginger can deliver more intense flavor with smaller amounts, though with a slightly different character than fresh ginger.

Best Ways to Use Ginger for Maximum Heat and Health Benefits

To maximize the benefits of gingerol, your preparation methods matter significantly. The highest concentration of active gingerol is found in fresh, raw ginger, making methods that preserve this state ideal for therapeutic purposes. However, different preparation techniques can be strategically chosen depending on your specific health goals and flavor preferences. For instance, incorporating garlic alongside ginger can enhance its health benefits.

1. Fresh Ginger Tea for Circulation Boost

Ginger tea represents one of the most effective delivery methods for gingerol’s circulatory benefits. By slicing or grating fresh ginger and steeping it in hot (not boiling) water, you preserve much of the gingerol content while creating an easily consumable form. The mild heat of the water helps release the compounds without significantly transforming them, providing a good balance of flavor and therapeutic effect.

For maximum circulatory benefits, consider adding a squeeze of lemon juice to your ginger tea. The vitamin C in lemon enhances blood vessel health and improves iron absorption, complementing gingerol’s vasodilatory effects. This combination creates a powerful circulation-boosting drink that’s especially beneficial during cold weather or after long periods of inactivity.

2. Ginger-Infused Honey for Soothing Throat Relief

Combining fresh ginger with raw honey creates a powerful remedy that leverages both ingredients’ antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties. To prepare, finely grate fresh ginger and mix it with raw, unpasteurized honey, allowing it to infuse for at least 24 hours. The result is a soothing, sweet-spicy mixture that can be taken by the spoonful or added to tea. Discover more about the anti-inflammatory properties of fenugreek as well.

This preparation is particularly effective for sore throats and coughs, where the combination of honey’s soothing properties and gingerol’s anti-inflammatory effects provides multi-layered relief. The honey also serves as an excellent preservation medium for the gingerol, extending its shelf life while maintaining potency.

3. Raw Ginger in Smoothies for Full Potency

Adding fresh ginger to smoothies provides one of the most efficient ways to consume it in its most potent form. Since no heat is involved, virtually all the gingerol remains intact, delivering maximum therapeutic benefits. Even a small amount—about a thumb-sized piece—adds significant potency to your smoothie while introducing a pleasant warmth that balances well with sweet fruits.

The bioavailability of gingerol may actually be enhanced when consumed alongside certain fats, making smoothies with yogurt, avocado, or a splash of coconut milk ideal delivery systems. These fats help with the absorption of the fat-soluble components in gingerol, potentially increasing its efficacy.

For a circulation-boosting morning smoothie, combine fresh ginger with citrus fruits, berries, and a small amount of healthy fat. This combination supports not only improved blood flow but also provides antioxidants that protect blood vessel integrity over the long term.

- Start with smaller amounts (1/2 inch piece) if you’re new to raw ginger’s intensity

- Freeze peeled ginger for easier grating and longer preservation

- Combine with pineapple for additional digestive enzymes

- Add a pinch of black pepper to enhance gingerol absorption

4. Pickled Ginger for Digestive Health

Pickled ginger, familiar to many as a sushi accompaniment, offers unique benefits for digestive health. The fermentation process involved in pickling may alter some of the gingerol content, but it enhances preservation while developing beneficial probiotic properties. The resulting product delivers a milder heat sensation while still providing digestive benefits, making it an excellent choice for consuming between or after meals.

Traditional pickled ginger uses rice vinegar, which adds its own digestive benefits through acetic acid content. This preparation is particularly effective for settling an upset stomach, improving nutrient absorption, and preventing the uncomfortable bloating that can occur after heavy meals.

5. Ginger Oil for Topical Circulation Benefits

When applied topically, ginger oil containing gingerol compounds can significantly improve local circulation. The warming sensation experienced when applying ginger oil to the skin represents actual increased blood flow to the area, making it beneficial for cold extremities, muscle recovery, and minor aches and pains. To make a simple ginger oil, infuse grated fresh ginger in a carrier oil like jojoba or coconut oil for several weeks, then strain.

For enhanced effectiveness, ginger oil can be combined with other circulation-boosting essential oils like black pepper or cinnamon. These combinations are particularly useful for massage applications targeting areas with poor circulation or recovering muscles after intense exercise.

Getting the Most from Ginger: Heat and Health Together

To truly maximize ginger’s dual benefits of culinary heat and health-promoting properties, consider integrating it into your daily routine in multiple forms. Morning ginger tea, midday cooking with dried ginger, and evening topical applications can provide continuous benefits throughout the day. The key is consistency—while a single serving offers immediate effects, the cumulative benefits of regular consumption lead to more significant long-term improvements in circulation, inflammation levels, and overall well-being. For those seeking natural ways to enhance their health, few botanical ingredients offer the impressive combination of culinary versatility and evidence-backed benefits that gingerol provides.

Frequently Asked Questions

The growing interest in ginger’s health benefits has generated many questions about its proper use, safety, and effectiveness. Below are evidence-based answers to the most common questions about gingerol and its effects on health.

Does ginger lose its health benefits when cooked?

Cooking transforms rather than eliminates ginger’s beneficial compounds. While some gingerol converts to zingerone and shogaol during cooking, these derivatives have their own health benefits—sometimes even stronger anti-inflammatory effects than the original gingerol. Gentle cooking methods like brief simmering retain more gingerol than high-heat techniques, but even fully cooked ginger maintains significant health properties. If your primary goal is maximum circulatory benefits, raw or lightly cooked preparations are optimal, but don’t hesitate to enjoy ginger in cooked dishes for a different but still beneficial compound profile. For more on the benefits of spices, check out the allspice health benefits guide.

How much ginger should I consume daily for circulation benefits?

Clinical studies showing circulation benefits typically use doses equivalent to 1-4 grams of fresh ginger daily, which translates to approximately a 1-inch piece of fresh ginger root or 1/4 to 1 teaspoon of ground ginger. Starting with smaller amounts and gradually increasing allows you to assess your individual tolerance and response. Additionally, you might find it interesting to explore the health benefits of allspice as a complementary spice.

For therapeutic purposes, this amount is often divided throughout the day rather than consumed all at once. Most people notice enhanced circulation effects when consumption is consistent over several weeks, though some immediate effects can be felt even after a single serving.

Can ginger interact with blood-thinning medications?

Ginger does have mild anticoagulant properties, meaning it can slightly inhibit blood clotting. While this effect is generally beneficial for cardiovascular health in healthy individuals, it could potentially enhance the effects of prescription blood thinners like warfarin, aspirin, or clopidogrel.

The risk of significant interaction is relatively low at normal culinary amounts, but higher therapeutic doses might have more pronounced effects. If you’re taking prescription anticoagulants, it’s advisable to discuss ginger consumption with your healthcare provider, especially if you plan to consume it regularly in supplement form or in large quantities.

Signs of potential interaction include unusual bruising, nosebleeds, or prolonged bleeding from minor cuts. If you notice these symptoms, consult your healthcare provider promptly while reconsidering your ginger intake levels.

- Normal culinary use (occasional small amounts) generally poses minimal risk

- Consistent high-dose consumption requires medical consultation

- Temporarily reduce ginger consumption before surgical procedures

- Consider timing ginger consumption several hours apart from medication

Is ginger’s heat sensation dangerous for people with sensitive stomachs?

Despite its warming sensation, ginger is actually gastroprotective for most people, meaning it protects the stomach lining rather than irritates it. Unlike capsaicin in hot peppers, which can sometimes aggravate sensitive digestive tracts, gingerol typically soothes the digestive system. In fact, ginger is often recommended specifically for digestive discomfort, including nausea, bloating, and indigestion.

However, individual responses vary. Some people with particularly sensitive systems might experience mild discomfort, especially with large amounts of fresh, raw ginger. If you have a sensitive stomach, start with small amounts in cooked form, which tends to be gentler. Ginger tea made by steeping thin slices in hot water often provides digestive benefits without overwhelming heat sensation, making it an excellent starting point for those with sensitivity.

What’s the difference between gingerol in ginger and capsaicin in chili peppers?

While both compounds create heat sensations and have anti-inflammatory properties, their mechanisms and effects differ significantly. Capsaicin produces an intense, localized burning sensation by strongly activating TRPV1 receptors, while gingerol creates a milder, more diffuse warming effect through more moderate receptor activation. This difference explains why chili heat feels sharp and concentrated, while ginger warmth spreads gradually through the body. For those interested in exploring more about similar warming spices, consider learning about cloves and their unique properties.

Physiologically, capsaicin’s effects tend to be more intense but shorter-lasting, often followed by a period of receptor desensitization (which explains the tolerance that develops with regular chili consumption). Gingerol’s effects are generally more moderate but can have longer-lasting systemic benefits, particularly for circulation and inflammation.